Every day, people battling obesity go into a doctor’s office where they’re told to lose weight, eat better, and exercise more. Perhaps they get a pamphlet or a few minutes of counseling. For far too many, that’s the end of it. Their care provider gives few, if any, practical strategies for shedding pounds or improving nutrition.

They go home, and left to their own (internet) devices they explore a parade of websites promising results in the form of strict diets, workout plans, or “revolutionary” drugs and supplements. The problem is, many of these “solutions” are not medically or scientifically sound. That’s troubling in a society facing an epidemic like obesity.

More than 7 in 10 Americans are living with overweight or obesity, which is a cause of numerous deadly conditions, including heart disease, stroke, diabetes, and certain cancers. That seems like reason enough for the medical profession to take it seriously.

Yet medical students spend, on average, just 10 hours on obesity education, according to recent research. That’s a blip compared to the weeks-long blocks students spend studying, say, the heart or the lungs. The same study found only 10% of schools surveyed reported that their students were “very prepared” to treat obesity. It’s no wonder people seek answers from outside the realm of medicine.

“I don’t think doctors have ever treated obesity, historically,” says Shauna Levy, MD, assistant professor of surgery at Tulane University Medical Center and medical director of Tulane’s Bariatric and Weight Loss Center.

“They don’t teach about weight management and obesity in medical school. Ask a third-year (medical student) what they did in year one and two, they say maybe one lecture, if anything – even though it’s one of the leading epidemics in our country, in the world.”

Was Obesity Treatment Hijacked?

This has led to a lack of understanding about obesity – among not only doctors but patients, policymakers, and society as a whole, with many still under the false impression that obesity stems only from laziness or a lack of willpower or intelligence, Levy says. Those are dangerous assumptions, she says, as there are many causes of obesity, and a knowledgeable doctor or specialist is the best option to sort through them.

“Obesity needs to be treated by a medical professional because it is a disease, just like high blood pressure is treated, diabetes, cancer, etc.,” says Levy.

“It's been outsourced to industry for so long that doctors have not been treating obesity. It's been Weight Watchers and Jenny Craig and SlimFast and all these businesses,” she says.

Too often, these companies have a singular or narrow focus, says Scott Kahan, MD, MPH, director of the National Center for Weight and Wellness in Washington, D.C. While some are shifting to new drugs, others remain fixated on diet, be it fasting, cutting carbs and fat, or boosting protein intake. This robs patients of options and feeds myths about willpower, he says.

“It’s sort of a popularity contest,” Kahan says. “It’s challenging for patients. They get siloed into this or that, this guru or that guru, this treatment or that treatment. This just isn’t a simple problem where if you find the right diet, that’s going to solve the problem. … If it were as simple as saying, ‘Everyone gets this medication and this diet and talks to this specialist,’ we would’ve solved this thing a long time ago.”

Because medical schools didn’t deem it important until recently, students, doctors and health care administrators haven’t prioritized it, he says.

“It’s a fair point that because there are commercial programs out there … that we’re just sort of shooing away patients to these programs. We don’t have to deal with it, which makes it easier not to have to focus on it,” Kahan says.

Obesity Is ‘a Team Sport’

Robert Kushner, MD, professor of medicine and medical education at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine, doesn’t begrudge weight loss companies. They merely “filled a gap and a void we should’ve been filling ourselves,” he says.

Though these companies can sometimes help people lose weight, it’s rarely an appropriate way to deal with a serious medical condition that poses risk factors for other diseases, says Kushner.

“With very few other medical problems do you call 1-800 to get help and get treated,” he says, explaining the risk of trivializing the condition’s seriousness.

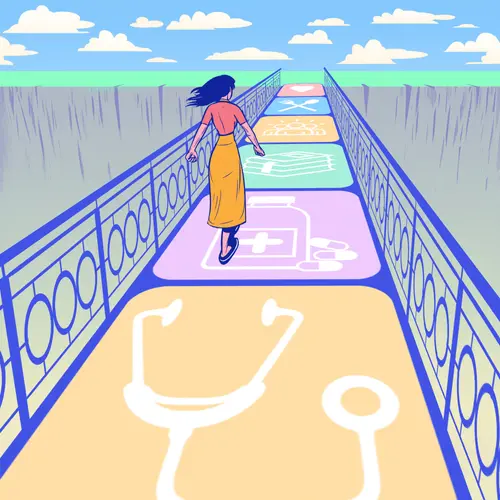

A top-notch obesity treatment program offers a comprehensive, multidisciplinary medical approach, which could include lifestyle modifications, medications, bariatric surgery, and everything in between, Kushner and Levy say.

Consider how “tumor boards” work. Rather than a single doctor prescribing cancer treatment, professionals from numerous fields – surgeons, oncologists, radiologists, pathologists, psychiatrists – confer to determine an individual’s best course. Likewise, obesity boards include experts on diet, nutrition, exercise, physiology, psychology, and sociology who can “triage” patients to the right specialist, Kushner says.

“Obesity I always call a team sport,” he says.

Unfortunately, comprehensive programs – such as those offered by Kahan’s or Levy’s centers or Northwestern’s Center for Lifestyle Medicine, which Kushner used to direct – are often found in academic settings and not always accessible to the average patient. Insurance companies’ reluctance to cover the full gamut of treatments poses another hurdle, Kahan says. While most private insurance companies and state Medicaid programs cover obesity screening, treatment coverage varies widely. For instance, an October 2023 study showed that while 3 in 4 employers covered GLP-1 drugs for workers with diabetes, only about 1 in 4 covered them for obesity.

Semaglutide, Tirzepatide and the GLP-1 Revolution

The GLP-1 drug boom is changing the landscape. Doctors are more engaged in treating people with obesity, due in part to the apparent effectiveness of these medications in reducing body weight. But there is a flipside to their newfound popularity.

Weight Watchers and Noom, which previously emphasized diet, now sell versions of these drugs. Telehealth company Ro has a deal with drugmaker Eli Lilly to distribute Zepbound. Even Costco and CVS advertise weight loss programs offering access to GLP-1s.

Meanwhile, celebrity endorsements and seemingly ceaseless advertising have led to drug shortages. Those have been filled not only by legitimate compounding pharmacies but also by online and fly-by-night wellness centers and med spas offering non-FDA-approved versions, which concerns Levy.

“People with limited to zero expertise in treating the disease of obesity, they’re just prescribing these medicines,” Levy said. “It feels like you could get it at McDonald’s.”

But the drugs don’t work for everyone, for reasons both financial and physiological. Their prices put them out of most consumers’ reach: About $1,350 a month for Wegovy and $1,059 a month for Zepbound (though Eli Lilly has reportedly released cheaper versions that are not covered by insurance).

They can also cause serious side effects for some, especially if used incorrectly. Levy worries, too, they’re billed as quick fixes and cure-alls, leading patients and doctors to forgo more nuanced, individualized, long-term treatment.

A New Path Forward?

Before we see the widespread adoption of obesity boards and multidisciplinary centers, there must be ample knowledgeable doctors to staff them. This goes back to the root of the problem: Medical schools simply haven’t prioritized educating future doctors on obesity.

Things are improving, if still lagging. Obesity medicine became a certification in 2012. As of 2023, there were 8,263 American and Canadian doctors certified. That’s a minuscule fraction of the countries’ 1.1 million doctors but more than three times the number reported in 2018. Still, obesity medicine is not recognized by the American Board of Medical Specialties.

National leaders have demanded an elevated focus on obesity and nutrition in med schools. One pillar of the National Strategy on Hunger, Nutrition, and Health calls for improving “nutrition and food security research,” and Congress passed a 2022 resolution calling for more “meaningful” nutrition education for medical trainees. Experts have also developed “competencies” – skills medical students must demonstrate and master – in obesity treatment and nutrition education.

Kushner is helping develop the obesity competencies and is part of the FORWARD program aimed at implementing and assessing obesity education curricula. Among the matters the FORWARD curriculum addresses are hormones, social factors, genetics, overcoming stigma and bias, sleep patterns, access to nutritious food, and even how to communicate with patients and their families.

Incorporating them is another matter. Medical school curricula are regimented and difficult to change, especially when professors are ill-equipped to educate students. Obesity also doesn’t fit tidily into an organ system like endocrine or respiratory, which is how medical school curricula are organized today – “so it has no home to fit into” even though obesity involves every organ system in the body, Kushner says.

Establishing comprehensive obesity care often requires local champions finding innovative approaches despite the system, he says. But it’s important to remember obesity is the “new kid on the block” and doctors’ understanding of the disease has been meaningfully evolving for only 30 or so years, compared to “decades and decades” for heart disease and cancer, he says. Kushner likened it to mental illness, alcoholism, and substance use disorder, which, similar to obesity, were severely misunderstood for years but are “now well embedded in medical education.”

“We just haven’t done that yet in obesity. … It’s a crowded curricula, and they’re not going to give up real estate to include obesity, which they really don’t know much about,” Kushner says. “We do have a dilemma: It’s one of the most significant health threats in the country and world, and we have insufficient education to prepare the students of the next generation.”